‘How did you start out as a writer?’ This question, or some variation of it, comes up at almost every book event Q&A, and no wonder: it’s a good question. Anyone who’s starting out as a writer themselves will be looking for a way forward, trying to find their bearings. And every author will answer differently. Although lots of them, particularly working-class writers, will include mention of public libraries. (The late Paul Auster’s answer to this same question is a gem of mid-20th century Americana BTW, and RIP.)

Regular readers will know that I usually post here about my books and book-related news. And don’t novels have to stand on their own?, detached – mostly – from the author’s biography? ‘The thynge yttself moste bee yttes owne defense’, as Bristol’s ‘marvelous boy’, the poet Thomas Chatterton puts it.

Well, yes. And I love that Chatterton quote – it’s from a ‘Letter to the Dygne Mastre Canynge’ in the front matter to his ‘Tragycal Enterlude’ Ælla (1769), ICYMI. But I’ve been asked that exact question about how I started out a dozen times or more in recent weeks: variously by students, by a writers’ group I gave a talk to, by a senior academic at a university I’ll be working with shortly, by an artist friend with a long memory, by a former Arts Council England colleague, and while guest-lecturing on a writing industry course for undergraduates just this week, etc. etc.

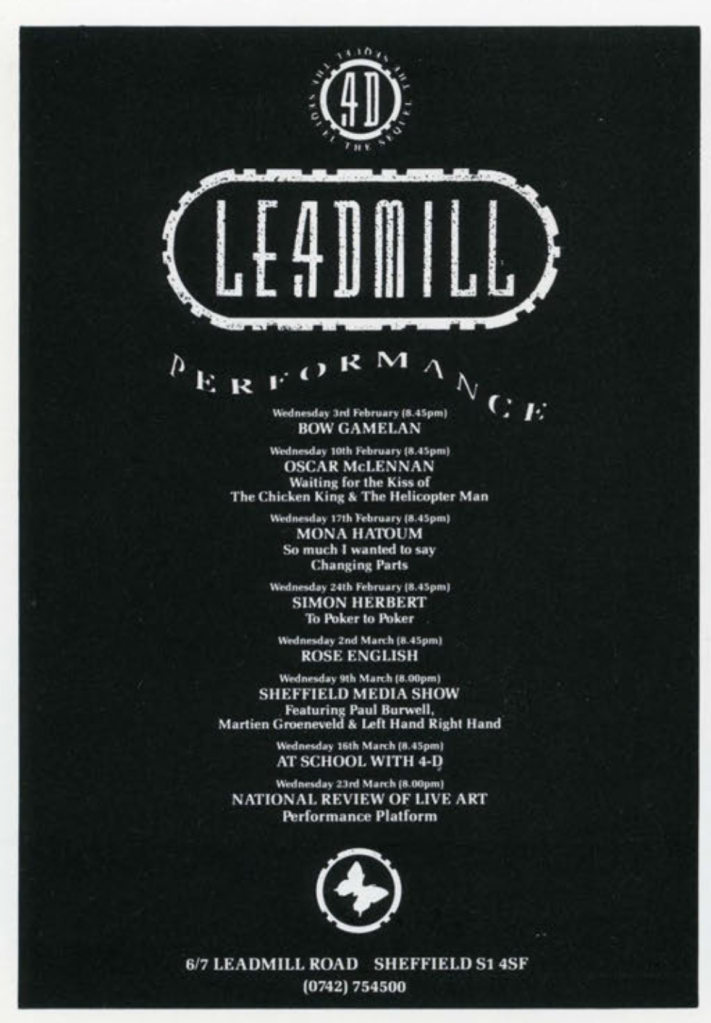

And coincidentally, recent news coverage about Sheffield’s celebrated venue The Leadmill, and some photos from my own archive, had reminded me of my answer.

TL/DR? I went the long way around, and discovered I was a writer by going to art school in Sheffield to study Fine Art and doing spoken-word performances at places like The Leadmill. Then at the beginning of the nineties all of that quickly mutated into writing prose fiction. How else?

The longer answer involves a conversation about access to arts education, class, Leeds and Sheffield in the eighties, and a view from the edge of the ‘performance art’ scene of the time, about a particular route into writing and becoming an author and discovering that prose fiction was where I lived, and was somehow the medium with which I had the most and the least control. It’s offered here since I keep getting asked, and in case it is of interest. But I know this kind of talk is not for everyone, so if that’s not for you, no worries. Thank you for reading this far. Normal service will be resumed shortly. See you around.

If you‘re still here, you probably saw that Leadmill coverage yourself: a dispute between management and the building’s new landlord, a ‘David v Goliath’-styled social media campaign, and a rally outside the Town Hall. The Sheffield Tribune published a slightly more critical alternative take, cataloguing some of the internal politicking, fallings-out, and transformations that have inevitably taken place over the years. Then in October 2023, Sheffield artist Martin Bedford sadly died. He’d designed many of The Leadmill’s distinctive gig posters over the years, and had been part of the organisation in its earliest days.

Like anyone who’s lived in Sheffield, The Leadmill has a special place in my heart. It feels like it belongs simultaneously to everyone and to no one. With all the major transformations that the city has undergone since 1980, it’s incredible it has survived in any form, and long may it continue.

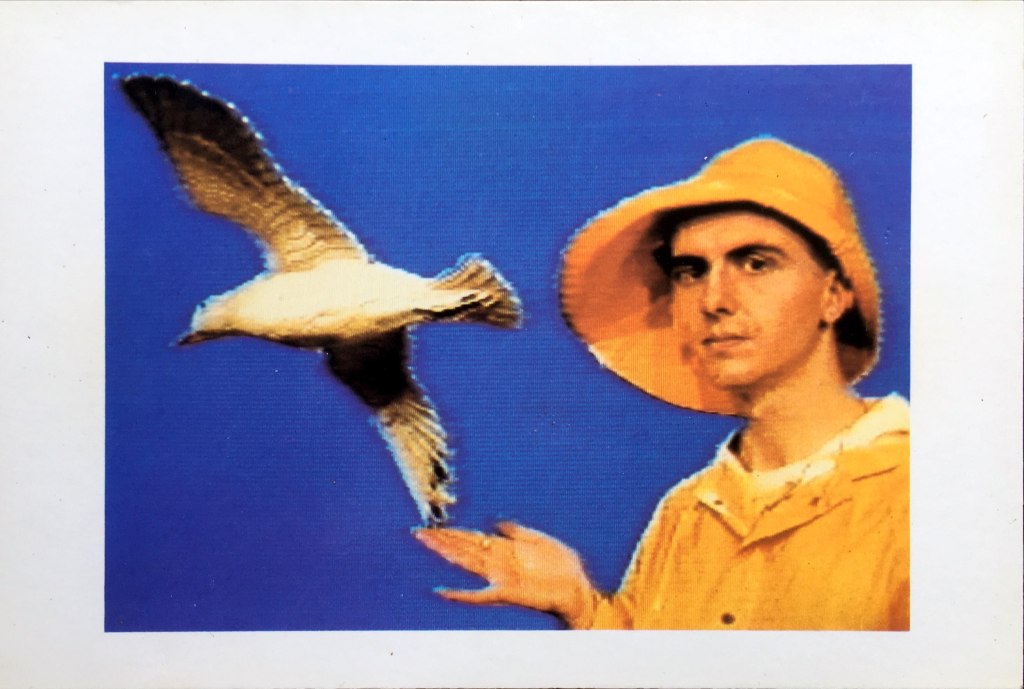

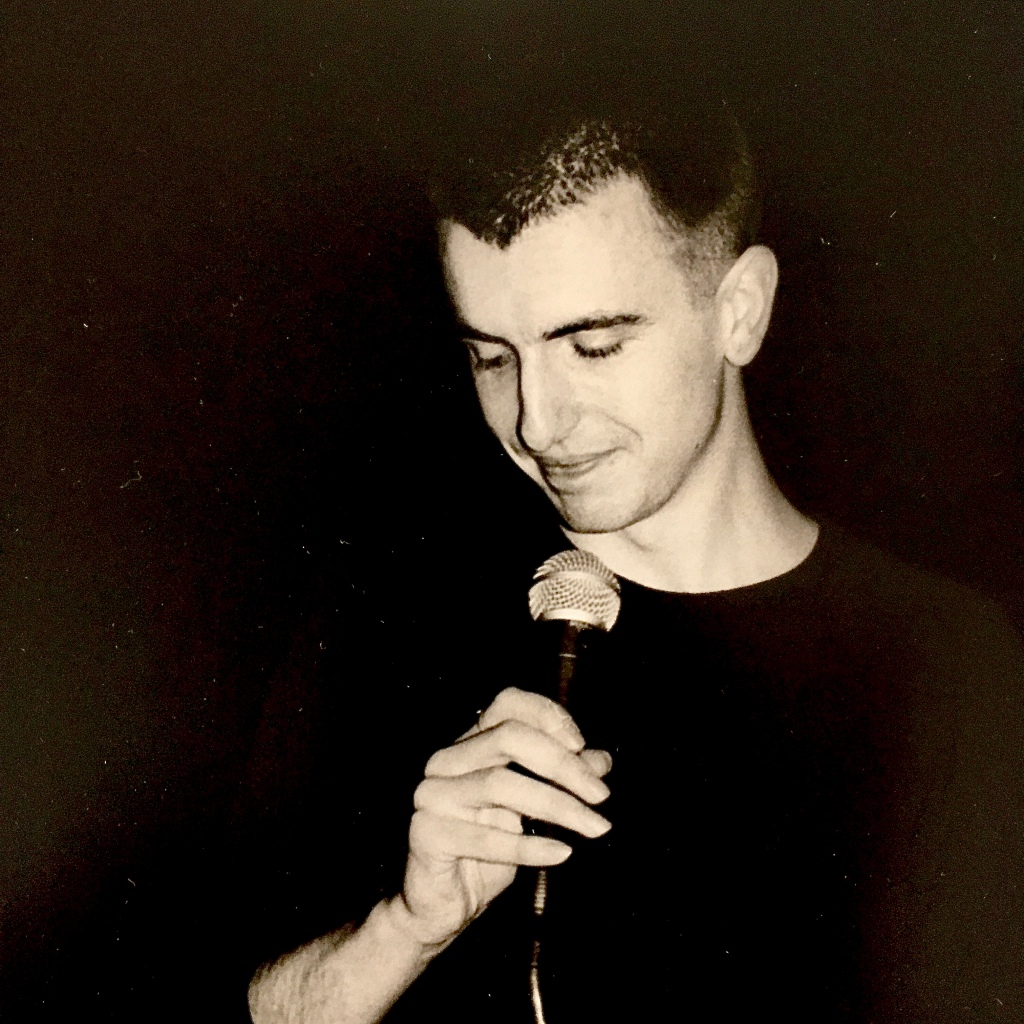

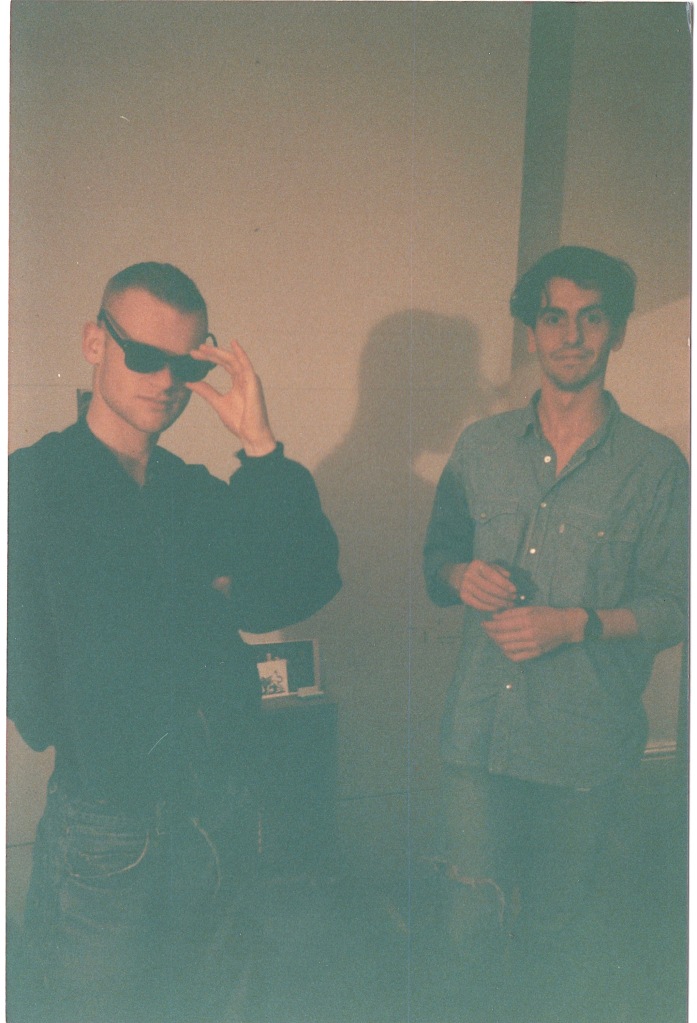

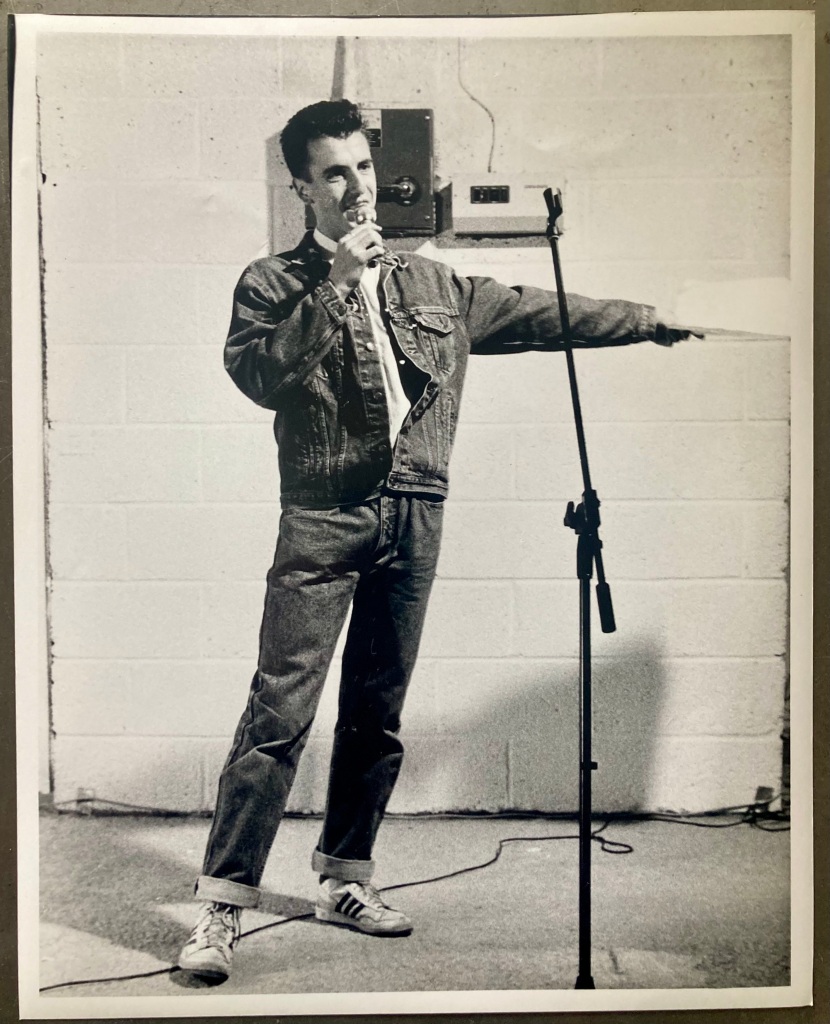

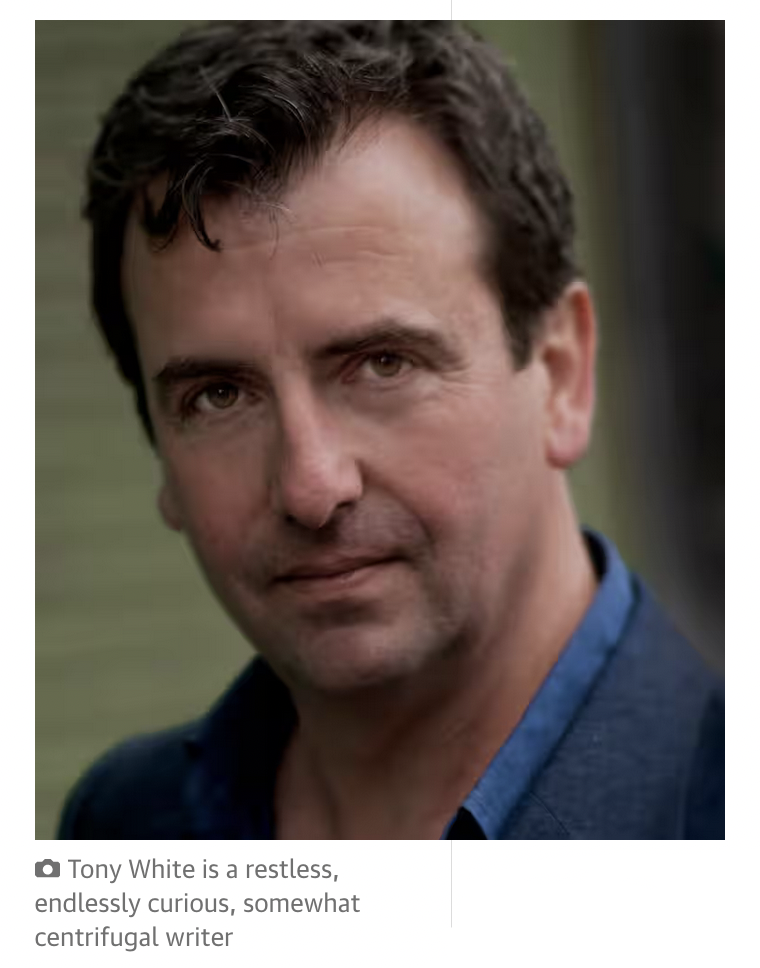

Here‘s a photo of me aged 23, performing there on 23 March 1988.

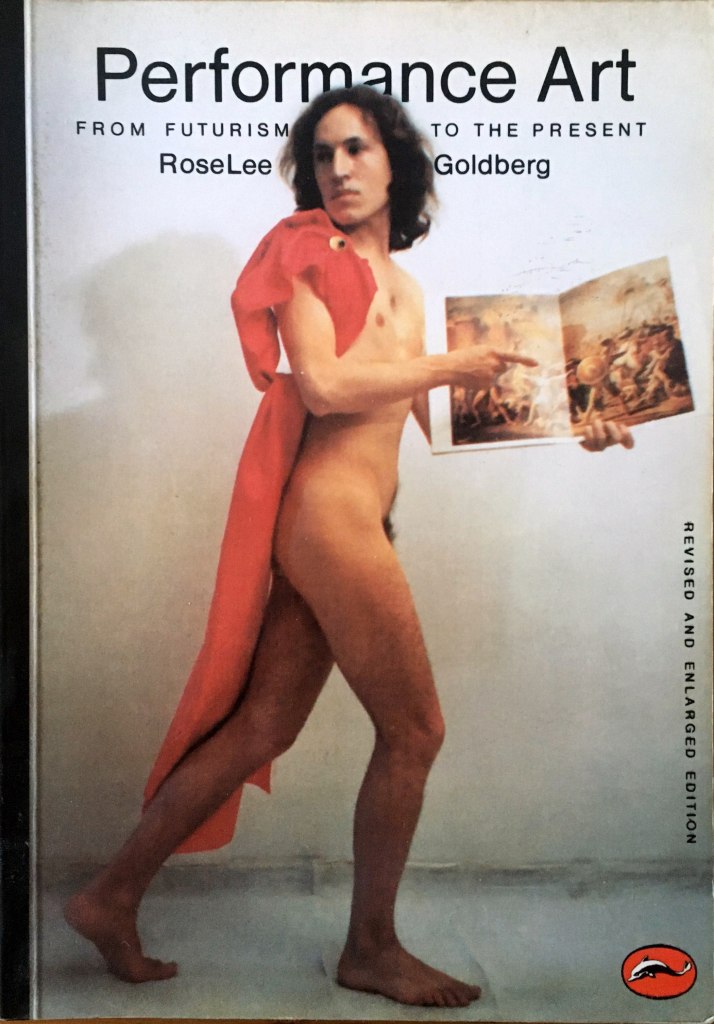

The event was billed (I just checked…) as a National Review of Live Art ‘performance platform’, and was part of The Leadmill’s then ‘4D’ weekly performance art programme. That’s ‘performance art’ in the senses discussed by RoseLee Goldberg here, or by Rob Gawthrop here, and with the additional pressure at The Leadmill of ultra-quick ‘get-outs’ needed to clear the dance floor for the House Music nights that would usually follow. This was not a slick piece of work. At the moment this photo was taken I’ll have been looking down to check my notes, or trying to remember what came next. (This performance wasn’t selected by NRLA director Nikki Millican to go on to a National Review that would take place at the Third Eye Centre, Glasgow later that year. But I didn’t mind, because I’d already performed off-the-bill at the previous year’s NRLA at Riverside Studios, London, alongside Roy Bayfield and the late Ian Smith, as part of Bayfield and Anne Seagrave’s officially-sanctioned ‘guerilla spoken-word programme’ – Roy’s words – in the Riverside bar.)

Q. What’s a photo of me performing at The Leadmill in 1988 got to do with my being an author now?

A. Everything.

It reminds me that every author will have found their own path to publication. And that anyone might be a writer, irrespective of age, class, and heritage (although looking around the publishing industry, that is not always apparent).

It also reminds me that there’s always a discussion to be had about wider access to arts education, the arts, and to the world of books and literature. Particularly right now, when roles in the arts, in Film and TV, and even arts education in schools, are increasingly being made the preserve of the already-privileged. It’s an issue that’s being addressed daily by artists (in the broadest sense of the word), teachers, venues, arts organisations, and funding agencies, by people working against the odds in the arts and humanities departments of universities and colleges (increasing numbers of which are either under threat or have already been cut), and by initiatives like Arts Emergency, the Class Festival, New Writing North’s Common People report, and its recently re-launched A Writing Chance programme, the artist Bob and Roberta Smith’s ongoing campaign that ‘all schools should be art schools’, and by community radio stations like London’s Resonance FM. There’s also the No-Entry Arts campaign on Twitter/X which speaks out against discriminatory age-limits on creative opportunities, and the poet Rachael Allen recently published an excellent piece about being working class and working inside publishing.

Becoming an author – even working in the arts more generally – was not an obvious career or life path for someone from my background. And many of the already precarious gateways that then existed to any kind of professional life in the ‘creative industries’ are fast being closed off to generations of working class young people today.

For me as for many people, those opportunities came from childhood access to literature in my local public library, and from arts education in schools – two vital areas of cultural provision in this country that are being or have already been removed, wholesale, from state schools and the public sector. And to films and music on TV, particularly the UK terrestrial channels BBC2 and Channel 4.

Speaking personally, it was also a stroke of luck to have been born and grow up in a small town with a big art school. It meant that ‘going to art school’ was a thing; a possibility. We’d even had art-student lodgers in our single-parent household for several years – which was demystifying in itself, and offered glimpses of the imaginative labour, time, dedication and enjoyment that went into creating things. And later, with the support of a great teacher named Anne Weeks who taught A-Level Art at Farnham Sixth-Form College (and who invited me to sit in on an A-Level Art History course I hadn’t known existed in time to register for) I got a place on the Foundation course at what was then the West Surrey College of Art and Design. It’s still there; now part of the larger University of the Creative Arts.

But even then, being offered a place doesn’t mean you can automatically take it up. Financial barriers to Higher Education are real (which is why I applaud this recent announcement from UCAS). In my case, even a nominal charge that became payable upon enrollment for the Foundation course at WSCAD was prohibitive (a token contribution towards the cost of equipment, IIRC). Thankfully, the college were immediately constructive, and offered a solution: free canteen lunches, and a cleaning job from 7–9 am every weekday morning, so the small charge could be deducted a couple of pounds at a time from my weekly wages. I accepted immediately.

With broom, dustpan, mop and bucket in hand, my patch most mornings was a stretch of the beautiful, purpose-built Painting Studio: a long north-facing, sky-lit, first-floor gallery, partitioned into individual workspaces, that stretched the length of the college site on Falkner Road, with curved, redbrick mural towers containing stairwells at either end that gave the main college building its distinctive silhouette.

Most of the other cleaners were third-year students trying to make a bit of extra money to pay for materials for their degree shows – a final exhibition that forms the central part of the degree assessment. So the job was a good way of connecting with the community. I heard on the grapevine that someone had a couple of spare tickets for Laurie Anderson’s United States I-IV at the Dominion Theatre, and space in a van driving up there both nights.

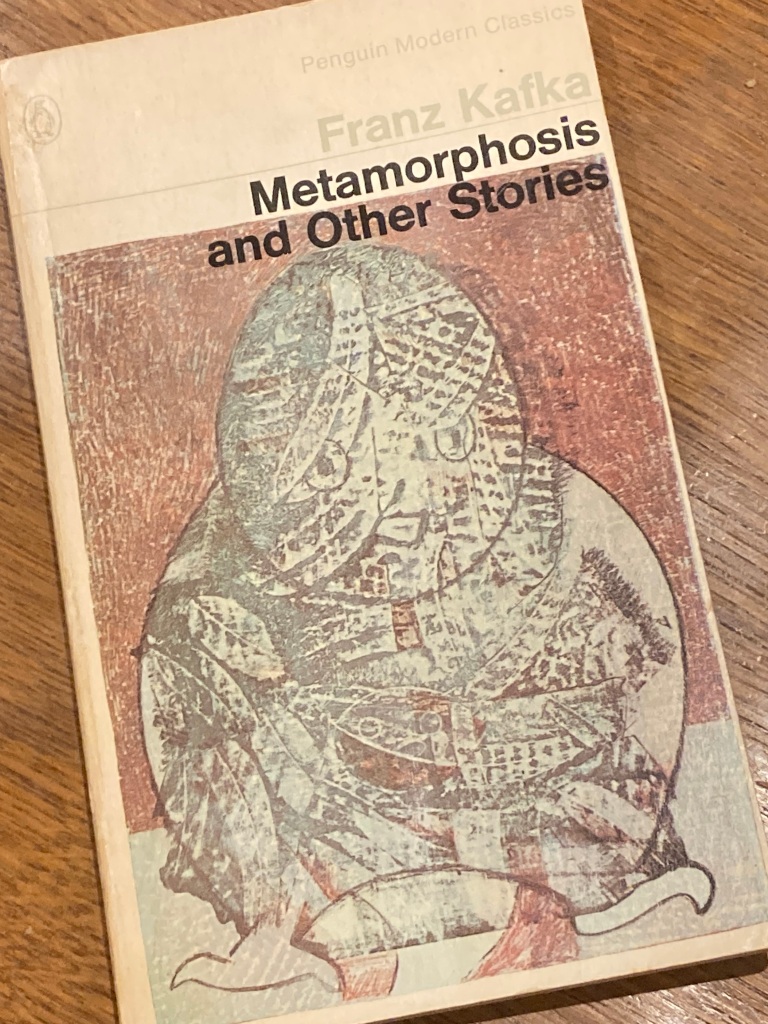

It was hard work, two hours’ worth of sweeping and mopping, but I enjoyed every minute. Until Franz Kafka got me sacked. I’d been completely transfixed by a Penguin paperback of Willa and Edwin Muir’s translations of Metamorphosis and other stories that someone had left on a workbench in one of the studios. The penalty for not sweeping the corners of the room properly for three days in a row was instant dismissal! Luckily I’d already paid off the enrollment charge by then.

After completing Foundation, I’d wanted to continue my studies without a pause, but my particular circumstances meant that before being eligible for the student finance of the day – the now legendary full grant – I’d need to be able to demonstrate that I’d been ‘self-supporting’ for three years. At a time when education was still seen as a public good, periods of unemployment actually fell within the definition of ‘self-supporting’ rather than being a disqualification. I moved to Leeds – had to live somewhere – signed on, and tried to stay focused, to keep reading, and to keep on seeing and making ‘work’, building up the obligatory portfolio. Until, two years later, with that eligibility threshold for a student grant finally in sight, I was able to apply to the then Sheffield City Polytechnic (what is now Sheffield Hallam University) to study for a degree in Fine Art, confident at least that if I got a place I’d now qualify for a grant from Leeds City Council. My mate Phil helped me haul all the work over to Sheffield on the train for the interview.

(I only noticed quite recently that access to education seems to have been a recurring theme in my fiction: from my novel Foxy-T to short stories including ‘A Porky Prime Cut’, and ‘High-Lands’ – maybe it’s not surprising. And incidentally, that particular route to studying as a ‘mature student’ no longer exists. A young working class person in the same circumstances today that I faced then would not easily be able to enter Higher Education.)

By the autumn of 1986 I was settling in to lodgings on Abbeydale Road in Sheffield. I’d had to start the first term of the degree course a month or so late due to illness, but a couple of Leeds friends had very kindly hired a van and moved my stuff for me. The first-year studios at ‘Psalter Lane’ (as Sheffield City Polytechnic’s then purpose-built art school site was known) were quiet because most of my year-group were on a field-trip to Amsterdam that I wouldn’t have been able to afford in any case. So I did the necessary grant admin, opened my first bank account, then mooched around the purpose-built college getting my bearings. Having a coffee in Psalter Lane’s famous canteen that afternoon I recognised the film maker Jayne Parker. I’d been to a talk and screening of her short film ‘I Cat’ at Leeds City Art Gallery earlier that year. Parker was there to do tutorials with second and third-year students, not first-years like me, but had some time to spare so said Okay.

I’d done a little writing in my Brudenell Grove bedsit in Leeds, aged about twenty; hammered out some prose sketches and slightly aimless cut-ups on a borrowed typewriter. Not much, but enough to sense something happening – a quickening in the text, that particular ‘coming to life’ – and to feel a new and subtle kind of agency and empowerment as a result. Although I’d been mainly entertaining the idea that at art school I would learn to make films, and/or ‘video art’ as it was called, and to that end I’d made a few very crude Super8 films on a Braun Nizo borrowed from my friend Martin Baker.

I must have rushed home and picked up a couple of those Leeds Super8 films to show Jayne Parker later that afternoon, but even with that slight distance (forty miles, and a few weeks) they’d already looked disappointing; quaint and boring, like the past and not the future.

And once I settled in at Psalter Lane, among a really great peer group of students (pretty sure I have a group photo somewhere, from the farewell dinner…), and taught by an inspirational cohort of artists, educators, and moving-image makers including Barry Callaghan, Steve Hawley, Frances Hegarty, Roger Wilson, and regular visiting artists including Alana O’Kelly, Nick Stewart, Andrew Stones, and Maud Sulter, it soon became clear that writing the idea down, writing it through, revising it, sharpening it up, wasn’t just a planning stage, the preliminary to booking half-a-day with a clockwork Bolex 16mm movie camera. It was the work itself. Kind of.

But at Psalter Lane we had access to state-of-the-art equipment: brand new Sony Video8s, darkrooms, a film studio, a recording studio, video edit suites, a black-box performance studio with lighting rig; all made usable by a brilliant technical team of Lynne Barraclough, ‘Nev’, Paul Gorman, Ronnie Hawksworth, et al. This was equipment that I’d go in early to use, as often as I could, as soon as the cleaners opened up the building in the mornings. I think I must have associated being at art school with early starts since my cleaning job at Farnham.

Even now, all these years later, starting work early is still part of my routine. Every writer finds their own way of doing things, and for me that’s how novels get written, by rising at 5:45 and starting work at 6am. I love that time of day.

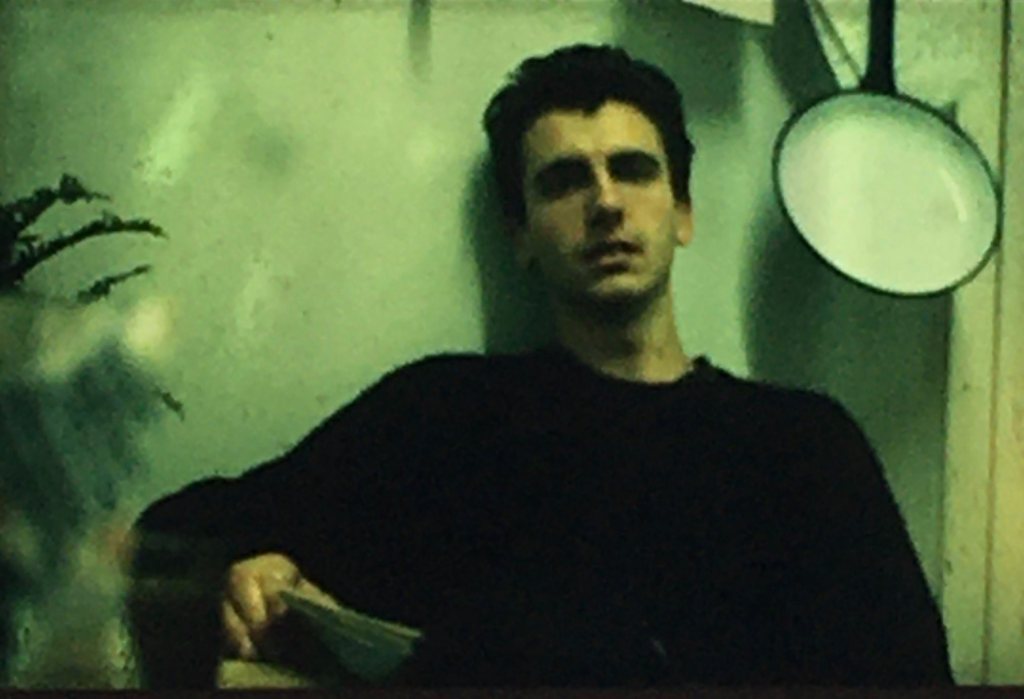

Here’s a selfie, 1988-style, shot on video in the film studio at Psalter Lane. That’s me aged 23, midway through the second year at Sheffield, with (in order to frame a tighter shot) a literal tip (or turn) of the hat to ‘Mr Wyndham Lewis as “Tyro”’.

Today you could create a more sophisticated digital image on your phone in a few minutes, but in 1988 it was not so easy. Here’s what you needed: access to an institution, lecturers, technical staff, a film studio, video camera, training, tapes, lighting, chroma key backdrop, U-matic edit suite, Fairlight digital effects generator, 35mm camera and tripod, and a roll of slide film or two to hopefully get at least one clean shot off the screen without horizontal banding – not to mention art-historical knowledge. The sou’wester came from a mail-order ship chandler in Grimsby. The seagull was a theatrical prop bought from an antique shop in Nether Edge where it had hung above the door. He sold it to me for £5.00, and promised to buy it back for the same price any time. (I never took him up on the offer.) The image was made for reproduction on a postcard: a kind of mail art come handout come publicity shot; overprinted on the reverse as needed. I’d had a few blanks left over when I first moved to London the following year, so would still have been using it as a calling card then.

That Koestler quote on the card… Even then, inspiration often came from words as much as images; from books bought at Hammicks in Farnham, from Compendium or Collets on trips to London, from radical bookshops like the Corner Bookshop on Woodhouse Lane in Leeds, or Independent Books on Surrey Street, Sheffield). Many of those books had been sought out specifically because of references in or on records, or in interviews in the music press: Laurie Anderson recommending books by John Dos Passos, Thomas Pynchon, and Gertrude Stein; Scritti Politti name-checking Jacques Derrida; Syd Barrett’s setting to music of a poem by James Joyce; Amos Tutuola via David Byrne and Brian Eno’s LP My Life in the Bush of Ghosts; William S. Burroughs via Throbbing Gristle, etc. (we’d watched Howard Brookner’s 1983 Arena documentary on Burroughs countless times on VHS in the W.S.C.A.D. library at Farnham), and from Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s own discussions and interviews in The Third Mind.

I took such recommendations and endorsements on board and sought the books out. More call-to-arms than mere reading-list; an invitation to wider, more eclectic, and closer reading.

I had a strong moment of recognition reading the late Mark Fisher, where he talks about discovering an interest in ‘theory’ from reading the NME:

No sob stories, but for someone from my background it’s difficult to see where else that interest would have come from.

Mark Fisher, ‘whyK?’, k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004–2016)

(‘No sob stories’, I like that.) It’s an idea that’s echoed and amplified in publicity materials for Simon Bedwell and Stuart Sutcliffe’s current exhibition of ceramic caricatures Memories of the Five Administrations (Beaconsfield, London, 15 May–22 June 2024): that they

are of the generation and social class for whom mass, state-funded education, TV and the music press, served as introductions to experimental art and European philosophy, as well as pop music and fashion. They suggest that recent governments have dedicated themselves to narrowing these possibilities.

Through the post-punk era, the music press and record shops had been places where the underground, avant-garde, indie, and mainstream converged: a multi-cultural ‘Library of Babel™’ open to all, in which records were both the thing and its index. The record sleeves were a vital source of information and reference, every word pored over: the networks of personnel and producers traced from one reggae and/or new wave record to the next; the living room gig photographed on the cover of The Name of This Band is Talking Heads (and details of commissions and stagings on David Bryne’s solo records); cottage-industry-style limited editions and fan ephemera; Mark E Smith’s fractured and visionary texts on The Fall sleeves.

In the mid-eighties I’d buy the Guardian every day, and do the Quick Crossword (little knowing that thirty years later I’d return to the exact same crosswords completed daily in 1985 and use them as an Oulipo-inspired source material now). By the time I was at Psalter Lane I’d also be waiting for the latest issues of Performance Magazine, Art Monthly, Artscribe, Artists’ Newsletter, and Independent Media magazines to arrive in the library every month, and read them all from cover to cover. We’d pass around The Face and i-D, precious copies of the slightly more esoteric and larger-format ZG, and Time Out if someone had been to London; piling up all the back issues for as long as possible, for future reference.

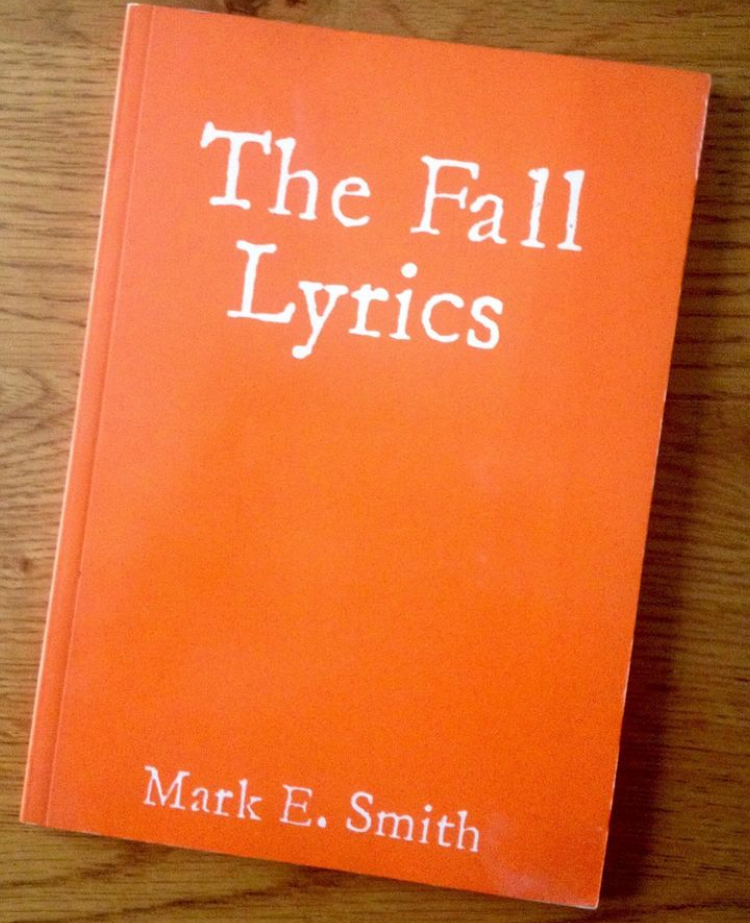

The small bookshelf I carried from one short-stay bedsit or house-share to the next centred on the unholy trinity of William S. Burroughs, Franz Kafka and Gertrude Stein, alongside a perhaps fairly standard(?) eighties mix of Calvino, Cervantes, Barthes, Borges, Pynchon, Tutuola, Kathy Acker, Martin Millar, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, William Gibson, Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Doris Lessing, Jeanette Winterson, Marcel Proust, Mark Twain, Wilhelm Reich, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Quentin Crisp, Koestler, Mervyn Peake, Michael Moorcock, Myles na gCopaleen, J.M. Coetzee. Paperback editions of monologues by Spalding Gray, and Eric Bogosian, and a book of The Fall lyrics I’d bought from the merch stall after a gig in the Mandela Building at Sheffield Poly on their Bend Sinister tour in November 1986. There was Helter Skelter, second-hand Ed McBain Penguins, and David Thomson’s Suspects. Culler on puns, Skretvedt on Laurel and Hardy, Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film, Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler, and the new translations of Baudrillard and Virilio in the Semiotext(e) ‘Foreign Agents’ series. A handful of art books: Paul Klee’s On Modern Art, bought from the bookshop at the Courtauld Institute, an ‘artist’s book’ of Truisms and Essays by Jenny Holzer that I’d picked up in the bookshop at Camden Arts Centre, a copy of Art After Modernism hunted down with some difficulty from the US, and a dog-eared paperback of RoseLee Goldberg’s Performance Art: from Futurism to the Present. And that was about it back then. I couldn’t afford to be a collector or a completist, never quite had that bug or the money to service it, but I’d long-ago learned to make a little go a long way, and besides I had access to college libraries.

As well as records and books, early inspiration came from visual artists and writers I’d seen performing live, or whose talks, lectures, screenings or workshops I’d been lucky enough to attend. The Foundation course at Farnham had offered a talks programme in the first term that seemed stunning at the time, let alone in retrospect, from artists including Ian Breakwell, Ivor Cutler, Bruce McLean, Stuart Brisley, Patrick Hughes, Bruce Lacey, Ron Geesin, Karn Holly (who also taught drawing on the Foundation Course), and Helen Chadwick (later a friend and neighbour in Beck Road, Hackney). I’d seen Laurie Anderson’s epic performance art work United States I–IV over two nights at the Dominion Theatre in 1983, and been the audience of one for Fiona Templeton’s You, the City; done workshops with Rose English, Paul Burwell, Tara Babel; seen performances by Seething Wells, Ted Chippington, and Kevin McAleer, and bought the spoken-word records of punk poet Joolz, John Cooper Clarke, and Linton Kwesi Johnson.

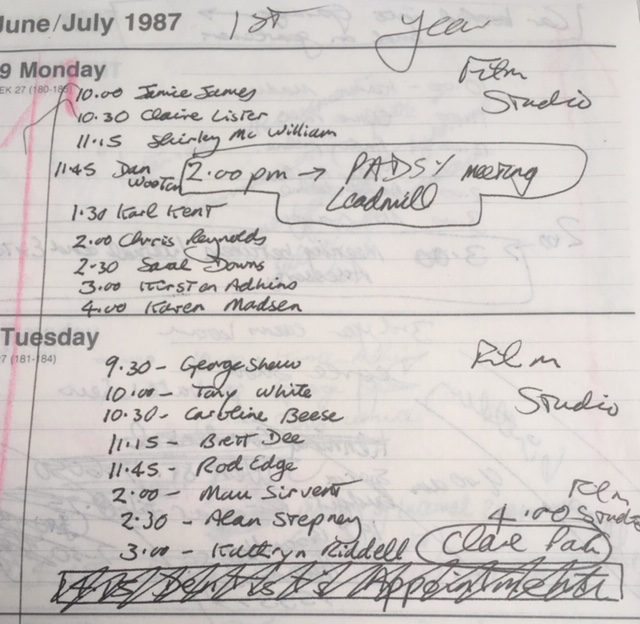

When I’d arrived in Sheffield it turned out that I’d just missed some performance art happenings on the streets of the city centre, but I heard the rumours, and saw an iconic photo of artist Nick Stewart walking through the ‘Hole in the Road’ with a tall sapling growing out of his backpack. The events were produced by a micro-agency named P.A.D.S.Y. – acronym of Performance Art Development in South Yorkshire. Later, on the recommendation of lecturer Steve Hawley, I joined Penny McCarthy and Sally Labern as a ‘student rep’ on P.A.D.S.Y. management meetings, backstage at The Leadmill, and got some insight into the production process, lead-in times and decision-making, and learned to write meeting notes.

Aside from Sheffield’s electronic music scene, its steel industry, and its art school, The Leadmill had been about the only other thing I’d known about the city before moving there. Still only a few years old, it was already legendary: a music venue in a former industrial building, run (at that time) as a cooperative, and where as well as the obligatory bar there was also a café opening right onto the dance floor, where you could get burgers, vegetarian food, and decent filter coffee – a highly unusual offer in the UK at the time.

Did I mention that bands and performers got fed in the Leadmill café? (I’d forgotten this, but Simon Beesley of the great June Brides reminded me when we got chatting at a book launch recently.)

But The Leadmill wasn’t only a music venue. In the words of Performance Magazine, it was ‘Sheffields (sic.) rock / community / performance centre.’ And its then arts programmer Caroline Bottomley had begun promoting full-on avant-garde performance art, under the ‘4D’ banner, showing works by artists including Neil Bartlett, Alastair MacLennan, Bow Gamelan, Tara Babel, Gary Stevens, Monica Ross, Anne Seagrave, Annie Griffin, Marty St. James and Anne Wilson, Mona Hatoum, Alastair Snow’s Orgreave-inspired ‘Guerilla Squad’, the Australian company Told by an Idiot, et al. It was all essential weekly viewing; a parallel education. Here’s an ad, found on the now-digitized Performance Magazine archive (with typography almost certainly by Designers Republic).

At that moment in Sheffield there was also a social and creative nexus of UK and international visitors and artists attracted to the city by the experimental theatre company Forced Entertainment.

The company – which when I met them in 1987 comprised Robin Arthur, Deborah Chadbourn, Tim Etchells (Artistic Director), Richard Lowdon (Designer), Cathy Naden and Terry O’Connor – celebrates its fortieth anniversary this year.

Already regular performers at The Leadmill, they were an immediate source (curious and generous) of creative exchange, strong leads, deep thinking and cameraderie that’s continued to this day. There’s happily been a lot of water under the bridge since then, in the shape of life-long friendships and occasional stuff like this, but here’s a snapshot of the period: Tim lending me novels by Michael Moorcock and Russell Hoban, and in turn me lending him my New English Library paperback of Hans Holzer’s Elvis Presley Speaks (…from beyond the grave); Cathy switching me on to Dickens, and Robin to Philip K. Dick; Richard helping me build props for my degree show (‘helping’ as in ‘building them’).

They’d bring news of emerging artists, reading and listening recommendations and exotic drinks back from UK and international tours that were also effective reconnaissance missions, with resulting intelligence shared over Tim’s home-cooked-vegetarian-curry-fuelled gatherings round at Penrhyn Road (often held in honour of a visiting friend/artist/promoter) or over a pint or two at The Washington pub. That was how a birthday gift of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, then just out in paperback, came my way; that Donald Barthelme’s late short story collections and David Bellos’s translation of Georges Perec’s Life a User’s Manual got added to my bookshelf.

A couple of dozen people would stick around at The Leadmill for Forced Entertainment’s ‘after-show discussions’ in those early days: there’d be the company of course (plus family members, and collaborators or extended company for a particular show), visiting UK or international promoters and artists, Caroline Bottomley and Graham Wrench from The Leadmill, John Avery and Jo Cammack from the band Hula (John did the sound/music for Forced Entertainment shows), me, Simon Crump, Tracey Holland, Alan McLean, Penny McCarthy, Karen Scott, Polly Thomas, and Jarvis Cocker.

Sat in a circle of chairs on The Leadmill dance floor after the Sheffield opening night of Forced Entertainment’s 200% & Bloody Thirsty (so, 14 November 1988), Jarvis said to Etchells,

Post-modern irony’s all very well, Tim, but what’s it got to do with getting off with someone in Castle Market on a Friday night?

Oh yes he did.

That’s the gospel truth.

(I’d seen Pulp performing at The Leadmill a year or two previously, not long after I’d arrived in Sheffield. It was an unusual gig, and I was going to include it here, but I think I’d better save it for another time.)

Such a great question! I can’t remember Tim’s response to Jarvis on that particular evening. But I was reminded by a conversation about Q&As on Twitter (and having been to numerous Forced Entertainment after-show discussions over the many years since) that the company members are great at treating every question from any audience member with dignity and respect, and answering sincerely and fully, no matter how many times they’ll have heard the same question. For any writers doing Q&As for the first time, it’s always worth remembering that even if you’ve heard a particular question half-a-dozen or hundreds of times at your events, for the person who has just plucked up the courage to ask it, this may be the first time they’ve had an opportunity to do so.

Anyway, such was the (ahem) crucible and the communities amongst which I was starting to write.

But it seems strange to reflect now, after nearly thirty years as an author, that with the short prose sketches, fragments, anecdotes and routines my art-student self was writing and performing prior to that, in the late-eighties, I’d had no thoughts of publication. And not just because the writing wasn’t good enough yet, though it certainly wasn’t. Publication hadn’t even crossed my mind as some far distant ambition. For me back then, books and magazines were things that other people wrote and which I read – albeit voraciously and constantly.

In that particular time and place, the most immediate way to make whatever I was writing ‘real’ seemed to be to read it to a live audience. My feeling was – probably still is – that an art work of any kind doesn’t really exist until an audience – whether viewer, reader, listener, witness – creates and completes it for themselves.

Which was precisely where the hospitality and openness of small, independent venues like The Leadmill of the time came in.

And not just The Leadmill. There was an annual student-run festival at Psalter Lane called The Sheffield Media Show, which was a big deal in its day: a destination festival capable of hosting Bill Viola premieres alongside artists both emerging and established, and student work from Sheffield, Cardiff, Hull, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Middlesex Poly, and more. (It was also informal enough that when I recognised artist Roy Bayfield milling around in the corridor at Psalter Lane at the 1987 festival, having seen him performing at the Zap Club in Brighton a month or two earlier, I could invite/persuade him to perform in the canteen later that evening.) Then there were return gigs put on by friends and peers at those and other art schools.

There were also venues, curators, artist-collectives, agencies, activists and promoters around the UK, including Lois Keidan at the ICA in London; Stella Hall at the Green Room in Manchester (which also hosted a regular artist-run night for emerging performers known as ‘The Quarter Club’, named for its origin out of 1987’s ‘No Quarter’ summer school; a partnership between the Green Room and Performance Magazine); the Air Gallery in London; the first ‘Contemporary Archives’ Festival in Nottingham (later renamed the NOW! Festival), and Geraldine Pilgrim at the Trent Polytechnic campus-based Powerhouse theatre-space; Projects UK programming festivals and standalone commissions in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, (and events at Newcastle Poly set up by then Fine Art students Vanessa Jones and Hester Reeve); the National Review, by now in Glasgow; Mike Stubbs at Hull Time Based Arts, etc. etc. A network of committed producers and makers fostering an emergent (but concrete, and – as I would find out – hospitable) performance art scene, a putative live art circuit that was documented and evidenced in arts-centre flyers, flypostings, and other marketing ephemera, with occasional newspaper coverage, with listings and reviews in the pages of Performance Magazine and Art Monthly, and (behind the scenes at the national office of the then Arts Council of Great Britain, later Arts Council England) in Jenny Walwin’s handwritten card-index record of the eighties UK performance art scene, noting meetings held, works seen (BTW I can confirm the existence and last-known whereabouts of this mythical item) and in policy documents like this one from the early nineties.

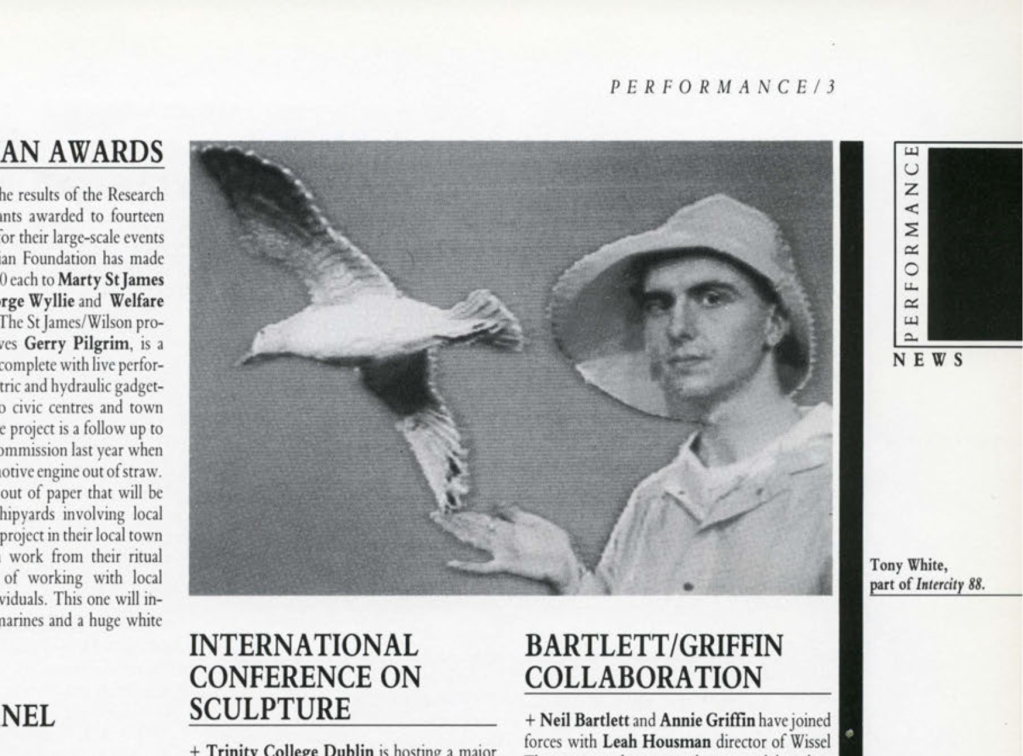

There was also a very active and activist artistic and creative scene across Sheffield at that time; in music and in the visual arts. Strong grass-roots collective action that in 1987 produced artist-led exhibitions in vacant city-centre shops; and the following year expanded into a two-city festival in empty shops, warehouses and studio buildings across Sheffield and Birmingham, entitled Intercity 88. (IIRC British Rail declined an approach for sponsorship, saying, ‘But you’ve already called it “Intercity” so we’re getting that for nowt!’)

For Intercity 88 I spent a week on trains between the two cities, gathering stories from the other passengers. And one week-day lunchtime I re-told a selection of those stories to a busy Bullring Shopping Centre, Birmingham, then a few days later in what would shortly become Sheffield’s first Waterstones Bookshop (in the newly-built Orchard Square), before taking it ‘on the road’ – not a tour as such, but a dozen dates around the country; a new way of working, and a premonition of the many gigs to come.

By this time, too, the world of print was starting to become demonstrably permeable; featuring words and images by or about people I was getting to know, or had seen around: work I’d seen, events I’d been at. And then my work started getting reviewed.

For me it was from early support and feedback of this kind, taking what I’d written and road-testing it in front of live audiences around the country that I learned I was actually… a writer.

(Albeit a ‘somewhat centrifugal writer’, as critic Sukhdev Sandhu put it in the Guardian recently, borrowing – I had to look it up – the literary theorist Northrop Frye’s formulation: centripetal v. centrifugal. Roughly: centripetal = moving towards the centre and/or focusing in on the text; centrifugal = moving outwards, and looking at the social context. Fair enough.)

At the end of the Fine Art course at Sheffield in ’89, the external examiner Professor Sarat Maharaj called a meeting in the H.A.D.A.F. building by the car park at Psalter Lane (H.A.D.A.F. = History of Art, Design and Film) to give feedback to those students who’d done well with their dissertations (the written component of the degree assessment). He went around the table, and when it came to my turn said something like, some combination of: This is quite elegantly written. Do you think you might be a writer? Something like that. A few gently future-facing words of encouragement, and surprising enough to make an impression. Because until that moment I hadn’t thought anything of the kind. I’m very grateful. I remember thinking, Haha, no! – but it turned out he was correct.

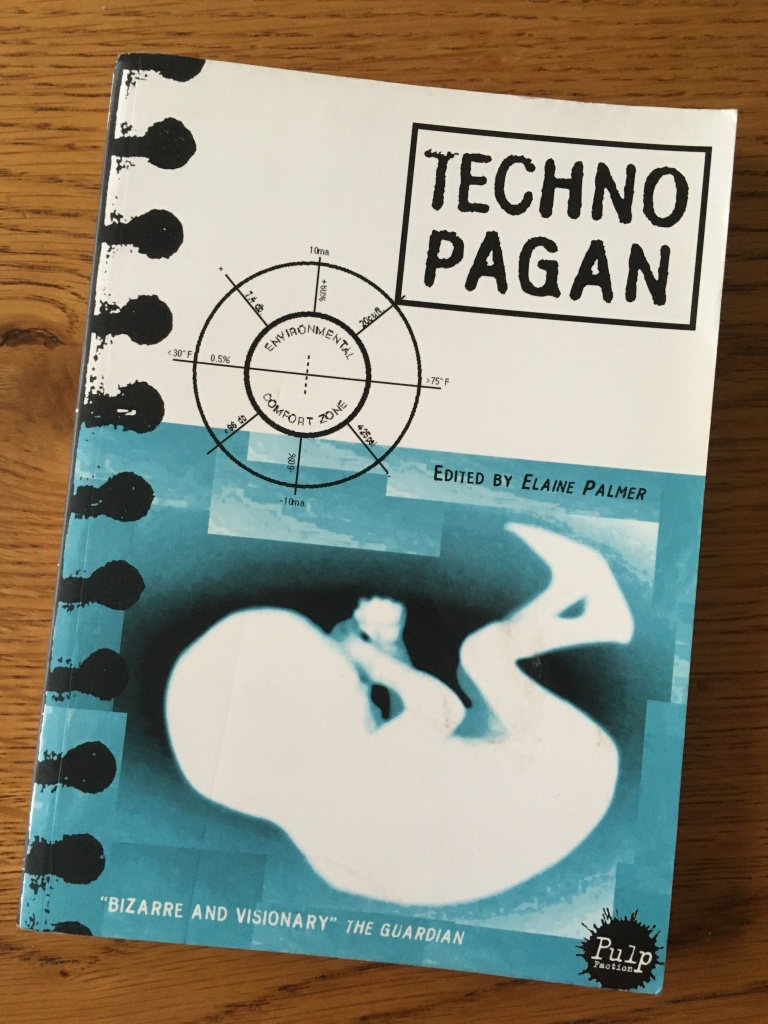

Although it would take a while, a move to London and a job in Foyles on Charing Cross Road, many more words written, a couple of false starts and abandoned drafts, and the discipline of regular reviewing, for his insight to crystallise, and for me to recognise it. Then there was a period from 1991–94 when, in turn, as ‘live art coordinator’ (a voluntary post that I juggled with childcare and a full-time job with Royal Mail) I produced a series of commissions, screenings and readings at a gallery called The Showroom, then in Bethnal Green, by artists and writers including Oreet Ashery, Anne Bean, Caroline Bergvall, Tim Brennan, Tim Etchells, Richard Layzell, Deborah Levy, Gordana Stanišić, Sarbjit Samra, Aaron Williamson and others. It took a couple of sideways leaps of faith and imagination, upgrading from a basic electric typewriter to a second-hand Amstrad word processor, and the inevitable catalogue of submissions and form-letter rejections, before the work did get good enough and my first short story was published in 1995. I’d submitted it to the second issue of an anthology/journal edited by Elaine Palmer called Pulp Faction, in response to a call in Time Out. The theme (and title of the anthology) was Technopagan, and I’d had a story that I’d thought might fit the bill. It wasn’t the first short story I’d written, there had been fifty or more before that, but when that one was published I could almost see what was wrong with the rest. I had a few goes at resuscitating them, but threw most of them away eventually (rash, I know, but necessary to keep moving forward), and in the meantime I cleared the decks and started afresh with what I’d learned.

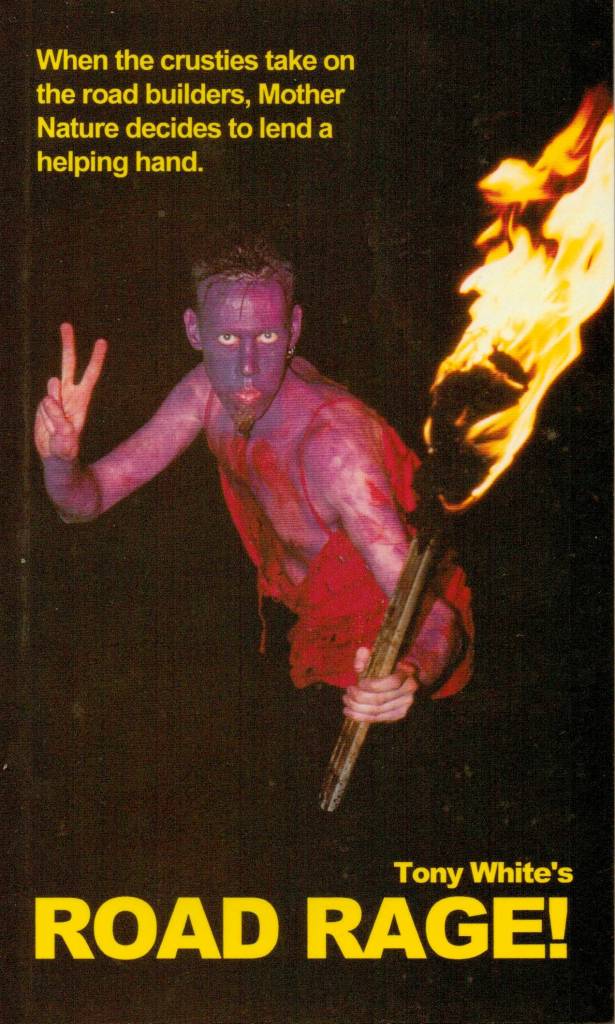

My first novel Road Rage! was written from an idea hatched in Endcliffe Park on a return visit to Sheffield in the late summer of 1995. Suddenly, my son had got a pre-school nursery place from 9:00–12 noon every weekday, which instantly opened up about 2.5hrs daily writing time that I seized with both hands (the Royal Mail had taught me to touch-type).

I was desperate not to waste this gift of free time, which might so easily have been absorbed with other things, so bashed out a chapter plan. Two-and-a-half hours each weekday morning turned out to be enough time and space to write the best part of a chapter a day. Within a few weeks I was revising a completed manuscript, then getting a final draft photocopied. After a number of rejections, I submitted the completed manuscript directly, i.e. un-agented, to a small press in Scotland.

I’d seen its publisher George Marshall interviewed on TV, alongside Dotun Adebayo of X-Press (which had been founded to publish Victor Headley’s novel Yardie, and was based around the corner from me in Hackney) and Stewart Home whose novel Red London was set around nearby Victoria Park and Mile End. Both of these – with their respective Richard Allen influences and recognisably contemporary East London settings – had been influences on Road Rage!, along particularly with Michael Moorcock, whose ‘Eternal Champion’ novels I’d been devouring in my lunch and teabreaks on late and early shifts at the Camden sorting office on St Pancras Way. Marshall had been republishing the Richard Allen ‘skinhead’ novels in new omnibus paperback editions, that were an early example of crowd-funding, though I’d been buying them as and when they came out. He’d started a paperback imprint called Low-Life Books to publish original fiction. I thought there was a chance he might ‘get’ a pulp novel written in the Allen-Moorcock mould about crusty road protesters in Hackney.

He did.

And he also told me that he thought my first novel wouldn’t be my last, which was why he put ‘Tony White’s ROAD RAGE!’ on the cover.

I’m eternally grateful for that faith he showed in me.

Thank you, George.

My debut novel Road Rage! was published on the Low-Life Books imprint, with a cover photo by my former Hackney neighbour Dave McCairley, in the summer of 1997 with a packed-out launch at a then groundbreaking bookshop and bar called Tactical on D’Arblay Street in Soho, almost a decade after the photo at the top of this piece was taken. I stood on the broad storefront window-seat to do a reading.

But it had been those early forays into spoken word and performance art a decade before, at Psalter Lane and at venues like The Leadmill, that had first given me a way-in to writing and to thinking about writing, and enabled me to find and begin to develop whatever fairly raw talent I may have had, and opened up the possibility in the first place.

And it is definitely because of those humble live beginnings, which quickly mutated into writing prose fiction, that all these years later ‘live literature’ (giving live readings from my books and short stories in all kinds of situations and contexts) remains a central aspect of my work as an author. I know that a lot of authors hate doing readings, but it’s what I do, and it connects with those early performance art and spoken-word influences and counter-traditions.

It may also be why I relish opportunities to collaborate with artists and musicians, as here for Glow: Santa Monica (Gibby Haynes!) or here at the TULCA Festival in Galway (New Pope!). It’s why my satirical police novel Charlieunclenorfolktango (1999) was first honed and aired as a spoken-word piece (premiering at this gig in 1997, ICYM). It’s why sometimes I’ll finish writing a short, key chapter of a novel or novella and think, That’s the reading!

It’s also why, if I have some one-off live event coming up, I’ll sometimes write a short story specially. Until quite recently I’d seriously assumed all authors did that, but it would seem they mostly don’t, the ones I’ve asked anyway. But some do: you should try it… That’s how several of my short stories got written: to be performed at particular events, including ‘A0’ for a lecture/reading at The Slade, ‘The Holborn Cenotaph’ for a collaborative event in Sir George Gilbert-Scott’s golden chapel at King’s College London, and ‘Plain Speaking’ for an online salon that just happened to coincide with the 110th anniversary of Flann O’Brien’s birth.

And I’m writing this now, six novels down the line (and the next in the pipeline), three novellas, and one work of non-fiction; dozens of short stories, anthologies edited or co-edited, scripts, residencies, and teaching appointments along the road, but that’s where the writing journey started for me. It was from a couple of years in the late-eighties of writing short prose sketches, anecdotes, and routines, and testing them in front of live audiences, then rewriting and testing again, and rewriting and so on, that the germ of a writing practice and a writing life was established.

Humble beginnings, like I said: the long way around. Grass-roots for sure, but real enough. Mostly juvenilia though, that eighties work, truthfully; I shudder to think, some of it. Growing up in public, and fast, as all writers do. But all of it – even taking the minutes at P.A.D.S.Y. meetings in a back room at The Leadmill – was a pathway to what would become a professional creative life that also included a decade working for the national office of Arts Council England. Craft and technique, editorial and mark-up, critical engagement, professional and production skills, performance chops were learned and developed, and the rudiments acquired of a way of living and working that usefully became knowledge and expertise, and which quickly grew in the early-nineties into wanting to stretch what I was writing. Needing ‘a bigger canvas to work on’, was how ex-art student me used to put it at the time, and finding it in the form, the duration, and the circulation of the novel and the short story.

And I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating, that without those opportunities as a young person, without access to public libraries, and to arts education (and, for me, the opportunity to go to art school, on the edges of the late-eighties performance-art scene) and that early support, the chance to learn from my mistakes via slots here and there from small, independent and innovative venues and programmers like The Leadmill at that time, which gave me opportunities to push my early writing and test it in front of audiences, and find my feet, there’s simply no way I’d be an author today.

Thanks, all.

But of course, it’s impossible to be asked this question of ‘How did you start out…?’ without at least registering the larger question of where future artists and writers in the UK will come from; or more specifically how and where working class and other underrepresented young people from marginalised or excluded communities will find and access the time and space to develop, the opportunities to discover and grow their interests and talent. It’s clearly vital to fight not only for public libraries, and for arts education in schools, and for the arts and humanities in higher education – under threat wherever you look – to support projects like Arts Emergency, the Class Festival, No-Entry Arts, A Writing Chance, and community radio stations such as Resonance FM, but also to fight against austerity; a decade-and-a-half (to date) of the ideologically-driven material impoverishment and running-down of communities, of vital public services, utilities and living standards in this country.

If, on top of that seemingly relentless and systematic impoverishment, if even the arts in the UK are now mostly to be made – God help us! – by the wealthy, by nepo-babies, by the entitled, by celebrities, and the already-privileged, then restricting curriculums and opportunities for working class young people to access the arts in schools, and to the arts and humanities in higher education, and to professional roles in the creative industries, just adds insult to injury: a failure of representation and imagination and opportunity – and policy on multiple fronts – that threatens to impoverish them and the rest of us still further.

§

Buy my latest novel The Fountain in the Forest direct from publisher Faber and Faber…

You must be logged in to post a comment.